For Chuma Somdaka, making art is not about drawing pretty pictures: it’s a way of finding peace, a way of talking with God. Every day, she sits on a shady bench on Government Avenue, right next to Parliament in Cape Town. Her portraits are spread around her for sale. She has her pastels ready. And she draws – draws passersby, draws the other people who live in the Company’s Gardens.

For nearly two years, this has been her home. Born in Mthatha, Somdaka grew up both there and in Cape Town, where her late father used to live. She was renting a room in Gugulethu when a man living nearby attacked her.

“He hit me with stones in my face, then tripped me, knowing that I’m amputated,” she remembers. She managed to get to her room. He told him if she didn’t come out by six, he would come and kill her. “I don’t know how it got into his mind that even had a right to do what he did. What also got to me is that people came out of the houses and were just standing there and watching”. She knew she had to leave – and so she took the train into town. The policeman she reported the attack to told her she didn’t have enough evidence to lay a charge. It was evening by then, and she had nowhere to go, and so she found a place to sleep at the bus terminus. It was her first night on the streets.

Somdaka’s mother lives in Mthatha, but she can’t go back there because she doesn’t see eye-to-eye with her step-father. Her head is still scarred from the 16 stitches she received aged 18, when he burst into her bedroom and beat her. “Later he said that my being a lesbian disgusted him and that was the reason he did what he did,” she recalls.

In the Company’s Gardens, “you’re visible daily – there’s no privacy. You see everything, and everybody sees everything of you,” she says. “What goes on in the Gardens is sex: sex in the toilets, sex in the bushes.” She talks about the man who lives in an Adderley Street hotel who comes to the garden almost every day to fuck homeless men. And then there’s the drugs: from six or seven in the evening, the junkies congregate, inhaling tik or smoking or spiking heroin. Sitting here, seeing all this, sent her into a slump.

“I was so frustrated. I thought what am I doing here, I’m just sitting here between people… there’s no love, no energy… it’s just all demonic, it’s just negative, it’s just people eating out of each other.”

And so last year Somdaka started drawing. “It was my let-go,” she says. “I find God in my art. It’s the same feeling, the same voice I used to get as when I used to hike up the mountain.” Drawing is “my haven that has some heaven. The minute I’m drawing, I’m able to forgive, I’m able to accept certain things, to evolve. I’m communicating difficult things that I find challenging. When I come out of there, the hunger is gone, it’s a beautiful world and I’m at peace.”

The last time she had made art was at a free workshop when she was 18. It unleashed hopes that she could embark on a creative career. But at a family meeting, her uncle told her that “Art is not something I’m going to survive on, being a black person. And why would I be drawing lines for the rest of my life, what is that going to do, because I have to think of financially supporting myself and surviving and that’s not going to make me survive. That was the end of art.”

Her fellow homeless sit “around me trying to figure out why am I doing art. To most of them it’s weird.” They want to know “Why don’t you use your [missing] leg to beg?” But she’s tried begging, and she hated it. For her begging “is like telling myself I’m nothing”. The time she attempted it, she stood there and realised: “I can’t.”

***

In the Gardens, sleep can be elusive. CCDI security patrolmen will occasionally pass through, hurling insults, telling the sleepers to get up and leave. When it rains, Somdaka takes shelter behind St George’s Cathedral. She avoids the front steps where most of the other homeless go – it’s too noisy and they’re “just going to bully you”. She tries to keep to herself. She’s learnt that it’s better that way. Months ago, she “got involved with the street 28 gangsters – in a friendship way”. She would look after their stuff while they were out on the streets. “I don’t know whether I blocked it out or was too naïve – but they were actually stabbing and killing and robbing people.” One day, one of the gangsters came up to her covered in blood. He had been attacked by the guy his girlfriend had been trying to rob. “I had to distance myself from that, because I didn’t want to be involved.” Another time, a gangster kicked her in the face and jeered: “Where’s your manliness now?” She went to a shelter in Paarl for a while but got tired of sitting around doing nothing. When she returned to Cape Town, she started sitting by herself, ignoring the hurtful comments the 28s made as they swaggered past.

If she doesn’t draw in the mornings “my day gets weird, she says. “It’s draining” knowing you can only get food at 11.30am from the Service Dining Rooms. It’s draining when passersby treat her with suspicion, like she’s a criminal. “There’s no humanity,” she says. “Some look at you as if you’re from I don’t know where – like you’re an alien.”

“Art makes it a whole lot better. It’s helped me to love.” She’s no longer bothered by a negative interaction because her art has taught her, “that it’s not about me, it’s about them.”

When she’s not drawing on her bench, Somdaka goes to the Central Library where a few of her artworks are on display. It is here that she’s become acquainted with her favourite artists – her beloved Vincent van Gogh, as well as Paul Gauguin, Juan Bautista Maíno, Derek Russell and David Hockney. When she’s not reading, she checks her email or works on her blog, which a friend helped her create. The website features both snapshots of her own life, along with mini-biographies she’s written about the people that she’s drawn.

“I don’t dream anymore. But I do hopefully hope,” she says. She hopes for social interactions between people “that engages with their humanity” – predicated not on the judging of appearances, but on listening. “Words can do so much,” she says. “They have the power to uplift.”

Chuma’s art in her own words

MR HEADPHONES

This is a city resident who often walks through Government Avenue. I was inspired to sketch him because of the expressions on his face while he listens to music. The expression on his face is determined by the asymmetrical design of his eyes and his narrow mouth. The well-lit face is framed by badly behaved hair, accentuated with restless brush-strokes and scratches. I drew this portrait with mixed media – wax, paint, charcoal and pastels.

This is a city resident who often walks through Government Avenue. I was inspired to sketch him because of the expressions on his face while he listens to music. The expression on his face is determined by the asymmetrical design of his eyes and his narrow mouth. The well-lit face is framed by badly behaved hair, accentuated with restless brush-strokes and scratches. I drew this portrait with mixed media – wax, paint, charcoal and pastels.

TUMI

I met Tumi a year ago and we became close friends. She often lives here with me on the street. She sometimes goes home and stays for few days but is always back. She shoplifts to support her heroin habit. She has been on it for almost 10 years and has been arrested three times since we became friends.

I met Tumi a year ago and we became close friends. She often lives here with me on the street. She sometimes goes home and stays for few days but is always back. She shoplifts to support her heroin habit. She has been on it for almost 10 years and has been arrested three times since we became friends.

Tumi has a teenage son who lives with her mother in Khayelitsha. She is also staying there at the moment because she recently came out of prison after being arrested two months ago. Last week she came to see me and tell me about what happened, and said that she thought it best that after speaking to me she should going straight home. Guess what? She did the opposite and went back to using. She looked so clean and healthy and had gained weight during her time in prison.

She sat with me so that I could do another portrait of her. I’m not happy about her smoking, but she is as stubborn as I am and there’s nothing I nor anyone else can do to make her stop. Her words are: “I am a heroin addict and that’s my drug of choice and it won’t change.”

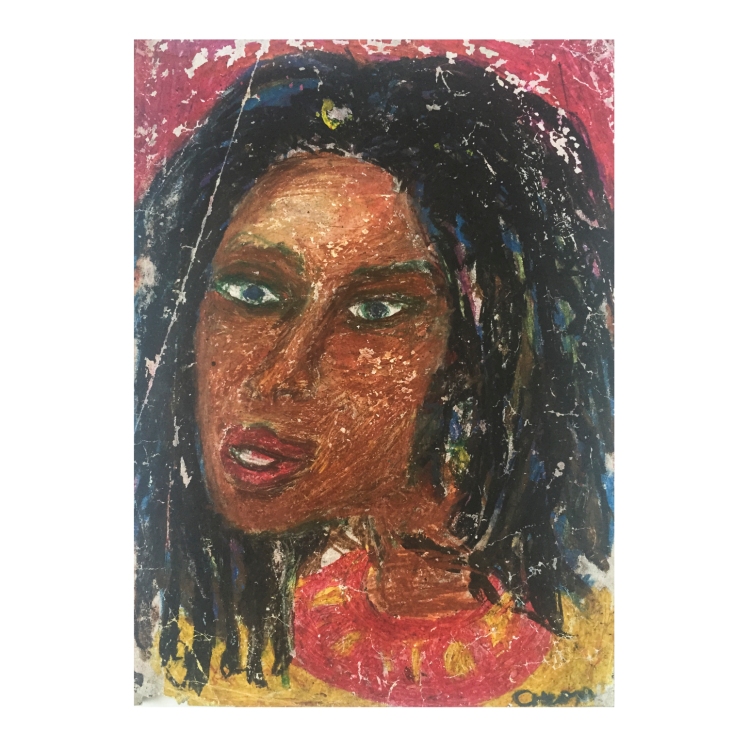

RASTA

Rasta is in his late twenties. He has a girlfriend who is HIV positive. She doesn’t take her meds and they are both tik addicts.

Rasta is in his late twenties. He has a girlfriend who is HIV positive. She doesn’t take her meds and they are both tik addicts.

Rasta is part of the 28 gang but recently he was beaten and almost burnt alive by them. If it wasn’t for his girlfriend, he would have lost his life. She pleaded with the new street 28 gang leader to let him live and in exchange she gives him the R1000 social grant that she gets every mouth. The gang said that Rasta must remove himself and break down his shack, and he is no longer welcome in the 28 camp, near Trafalgar High School. Ever since then he has been on the run and no one knows where he sleeps, but we suspect it’s some way up near Table Mountain.

DIKIE

Dikie is a homeless man who’s been living on the streets of Cape Town for 40 years. I’ve grown fond of him. He makes a living by resourcefully collecting cardboard boxes where he can, then exchanging them for cash at the Service Dining Room. He has lost two sons to TB. He is very shy, and as I know him, he usually just quietly greets you, but is mostly on his own.

Dikie is a homeless man who’s been living on the streets of Cape Town for 40 years. I’ve grown fond of him. He makes a living by resourcefully collecting cardboard boxes where he can, then exchanging them for cash at the Service Dining Room. He has lost two sons to TB. He is very shy, and as I know him, he usually just quietly greets you, but is mostly on his own.

His behaviour can be confusing. He is a man of few words, yet the moment he opens his mouth all he speaks about is who and how and when he last had sex. Dikie is honest about his sexuality and tells me that he enjoys being with men. I have even witnessed him having sex.

This portrait was done in the late evening when he surprised me with a gift on my birthday. I sketched him using a stick that I burnt to create charcoal. I prefer to use this method when I begin drawings. One of the reasons that I draw people’s faces is because I believe that the truth reveals itself. Even though you may not see their thoughts, their impressions and eyes and energy give a clear insight to the true being.

An edited version of this story appeared in the 18 December 2016 edition of the Sunday Times. The photographs were taken by Sarah Schäfer. To buy a portrait, email Chuma. She also now sells her artworks, along with prints and cards, at the Good Company Farmers’ Market in the Company’s Gardens every Saturday.

You are an inspiration. May God bless you. I pray that you will soon have a roof over your head.

We have set up an exhibition of her work where she will talk on 3 different nights on 3 different topics. From there you can get to know her better, buy her art and donate into the Kickstarter account.

Please will you help us get her established off the street as a talented artist!

https://www.facebook.com/events/171630946654591/