It is almost six months since the dramatic departure of Robert Mugabe from Zimbabwe’s presidency. As more than 100 political parties gear up for elections in July, citizens’ hopes for the future range from cautiously optimistic to fiercely sceptical.

“We can’t speak of much actual progress, but we can speak of lots of encouraging promises,” says John Robertson, a veteran economist based in the capital.

He is confident Zanu-PF will remove impediments to investment but concedes that in spite of “assurances that everything is going to be different, we’re still waiting for the actual changes to legislation and regulations”.

The most significant of these changes is the granting of bankable and transferable 99-year leases to black and white commercial farmers — whose position remains precarious. The promised change to indigenisation legislation, which requires foreign owners to hand over 51% of their companies to black Zimbabweans, is also still pending; the amendment will limit these requirements for platinum and diamond mines.

After the eviction of thousands of white commercial farmers, the agriculture sector struggled and Zimbabwe — once “the bread basket of Africa” — became a net importer of food. Reviving agriculture will be essential to supply factories with inputs such as cotton for textiles, timber for paper and vegetables for processed food.

If the manufacturing sector is revived, Zimbabwe should see increased exports and a drastic reduction in imports, improving the balance of payments.

Though tackling corruption and reforming loss-making and grossly inefficient state-owned companies will be difficult, Robertson says, “over the next five-10 years I think we’re going to see a lot of the lost ground made up. There will be dramatic differences in this country.”

The fear factor has been removed. “The government of Mugabe was oppressive, and people felt under constant threat of being bullied or punished for showing disloyalty to the ruling party. That disappeared overnight,” Robertson says.

“That’s made a very big difference. It’s a very important component of the improvement we have enjoyed.”

University of Zimbabwe economics professor Tony Hawkins offers a more sobering assessment. In the period after the election there will need to be discussions about “hard economic realities which no one is talking about”, he says.

To meet the requirements for assistance from multilateral institutions such as the IMF, he believes there will have to be “sharp cuts in government spending and layoffs” across a public sector that employs just over half of the employed workforce outside agriculture and which swallows up more than 80% of government revenue.

Growers receive $390 a tonne for maize — roughly $240 more than the average world price; these subsidies as well as ones for fuel will have to end.

A shortage of hard currency because of a reliance of imports has led the government to printing bond notes, which are officially pegged to the US dollar but in reality trade at 40%—50% less on the black market. If this continues to widen as Hawkins predicts, de-dollarisation will become inevitable, resulting in an initial period of high inflation.

He describes Zimbabwe’s debt situation as dire. In addition to $11bn of foreign debt (about 60% of GDP), there is $6bn of domestic debt With savings wiped out by the hyperinflation that led to Zimbabwe abandoning its currency and adopting the dollar in 2009, it’s likely the country will be forced to borrow more to pay its World Bank bill and keep the Paris Club of creditors happy.

Hawkins estimates that to create 60,000 jobs, inflows of $6bn a year would be required, but even this will fail to soak up the 200,000 graduates pouring out of schools each year. This results in a “very divided society — of those on the inside and those on the outside”.

Glenn Stutchbury, until recently CEO of Cresta, one of Zimbabwe’s largest hotel chains, remembers that at the height of the hyperinflation that caused the Zimbabwe dollar to be abandoned, he was forced to pay his staff with bread and other essentials because money had become worthless. Victoria Falls, the country’s biggest tourism drawcard, was a ghost town, its hotels and lodges largely empty.

Today, thanks to the opening of a shiny airport with new international connections, the town is buzzing. Mugabe’s departure has, in particular, helped to attract UK visitors who have long avoided visiting the country.

Though new rooms are being built, Stutchbury predicts a shortage of beds during high season in Victoria Falls, with increasing numbers of foreign visitors travelling on to the nearby national parks.

Bringing in almost $1bn of foreign revenue, tourism is a quick win in helping to revive the moribund economy, Stutchbury says, “because you don’t require huge inputs” needed by sectors such as manufacturing and mining.

Investment interest is key to driving commercial tourism in any country, Stutchbury says.

In Harare business travel has experienced a spike since November as potential investors flock to the capital.

No new hotels have been built since the early 1990s, but Stutchbury says that this will soon change, citing interest from both the Hyatt and the Radisson Hotel Group.

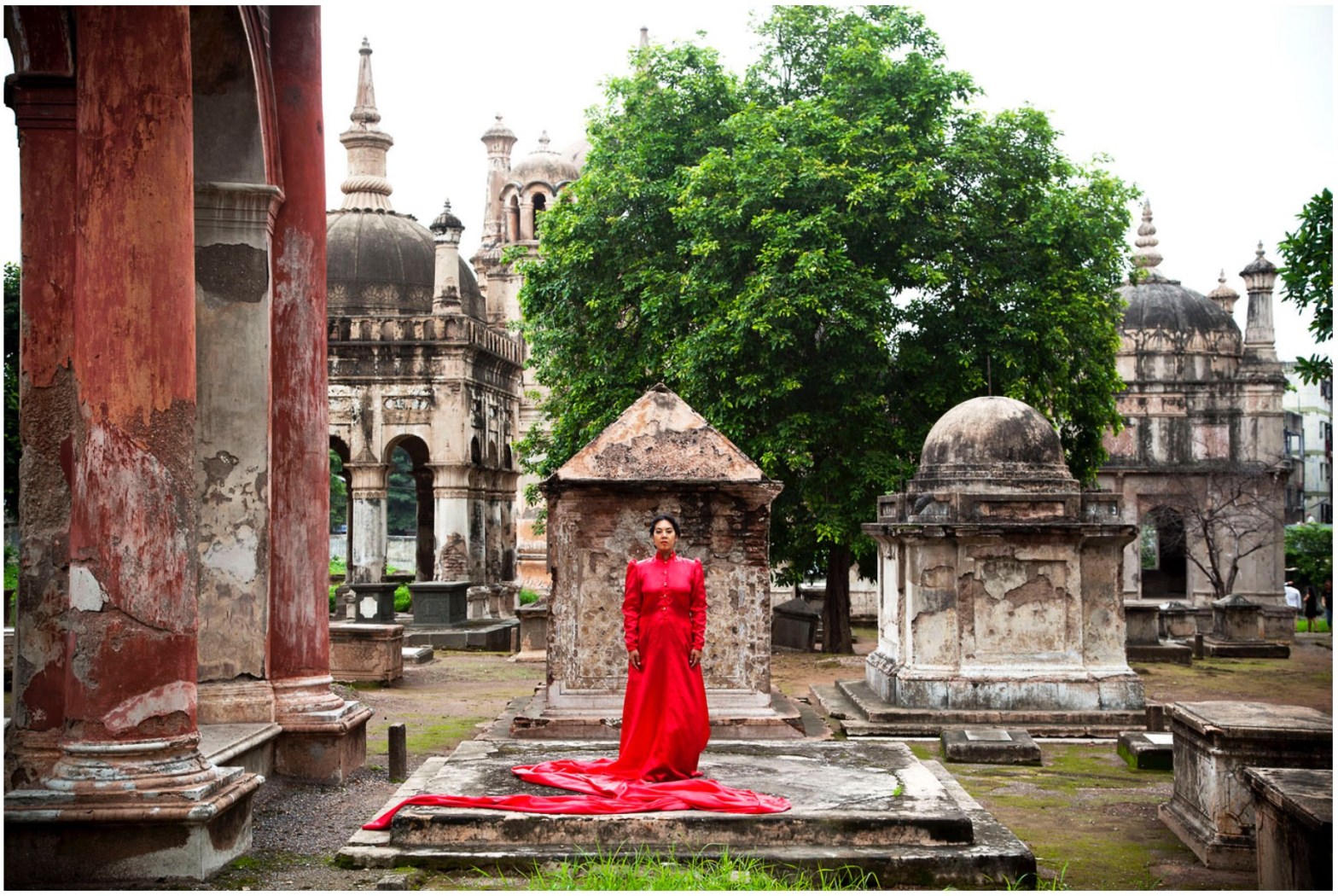

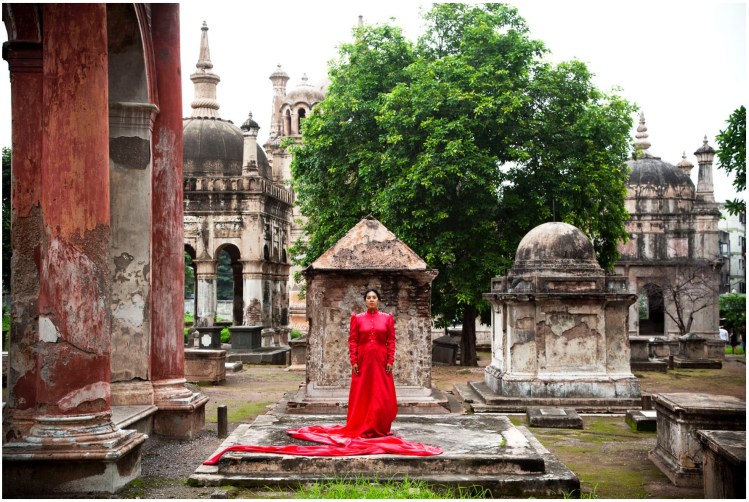

Since it began participating at the Venice Biennale in 2011, Zimbabwe has been making waves in contemporary art. Several artists are now represented by commercial galleries in SA and the UK.

“Artists have not given up the struggle,” Raphael Chikukwa, chief curator at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, says. Due to the shortage of art materials, “they have found new ways of expressing themselves”.

The gallery oversees the Venice pavilion; its sleek but dilapidated modernist building in downtown Harare is also home to an arts school.

Following Mugabe’s ouster, Chikukwa predicts a burst of creativity and an abandonment of the self-censorship that was prevalent during his rule.

As Zimbabwe’s frosty relations with Britain and the EU start to thaw, the gallery’s role, he believes, will be to foster increasing opportunities for Zimbabwean artists to be showcased internationally.

Chikukwa is in discussions with British curators about possible exhibitions in the UK.

With improved access to funding likely, he also hopes Zimbabwe will increase the number of international events it participates in.

For Violet Mazvarira, the pouring rain is both a blessing and a curse. Without irrigation, it’s essential for her crops to thrive. But it leaks into her ramshackle mud hut, making her blankets sopping wet.

A widowed former school teacher, Mazvarira has lived at Manzou Farm since 2000 when its white owner was evicted. She tills her 4ha with a hoe; only her son helps her. Since 2012, the police have come to demolish her house seven times.

“Grace saw this place is rich,” she says, referring to the former president’s wife, who flouted court orders with various attempts to evict Mazvarira and the 120-odd other people who are living here.

Though Mugabe tried to establish a game park on the land, Mazvarira believes she was more interested in the farm’s gold deposits, which artisanal miners have been exploiting for at least a decade.

Though police harassment has stopped since the Mugabes’ fall from power, Mazvarira worries that without an offer letter (a certificate that identifies her as entitled to farm) harassment may one day resume.

“We are still suffering. There’s no clinic, no schools. We want good living conditions,” she says.

She wants the government to sponsor pesticide and equipment —, complaining that the only assistance she received in 2017 was 10kg of maize seed. She’s not optimistic about receiving help, however.

“The same government is still there,” she says. “Maybe I’ll be happy in heaven.

“But not here on earth.”

This article first appeared in the 20 April 2018 edition of Business Day.