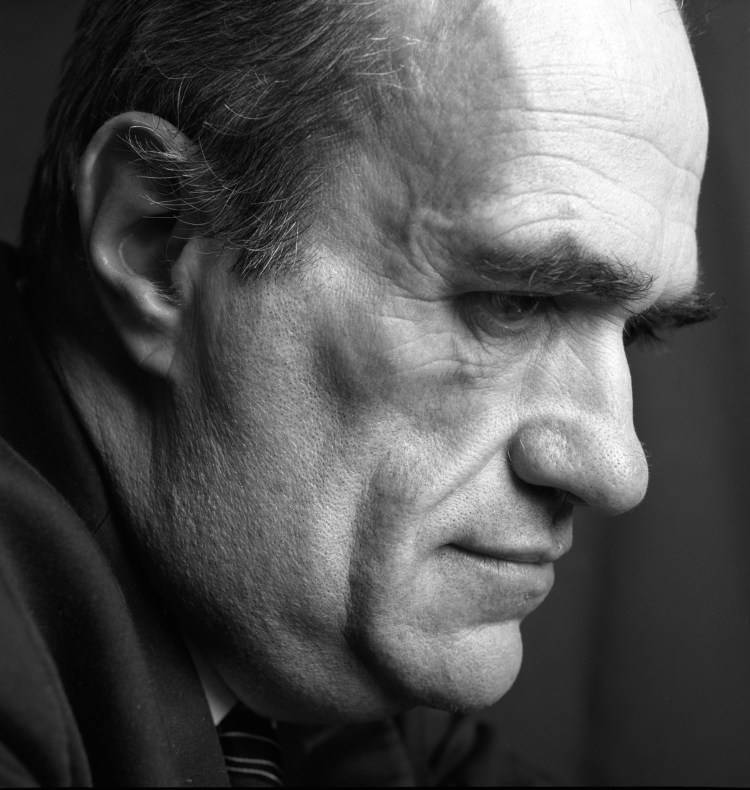

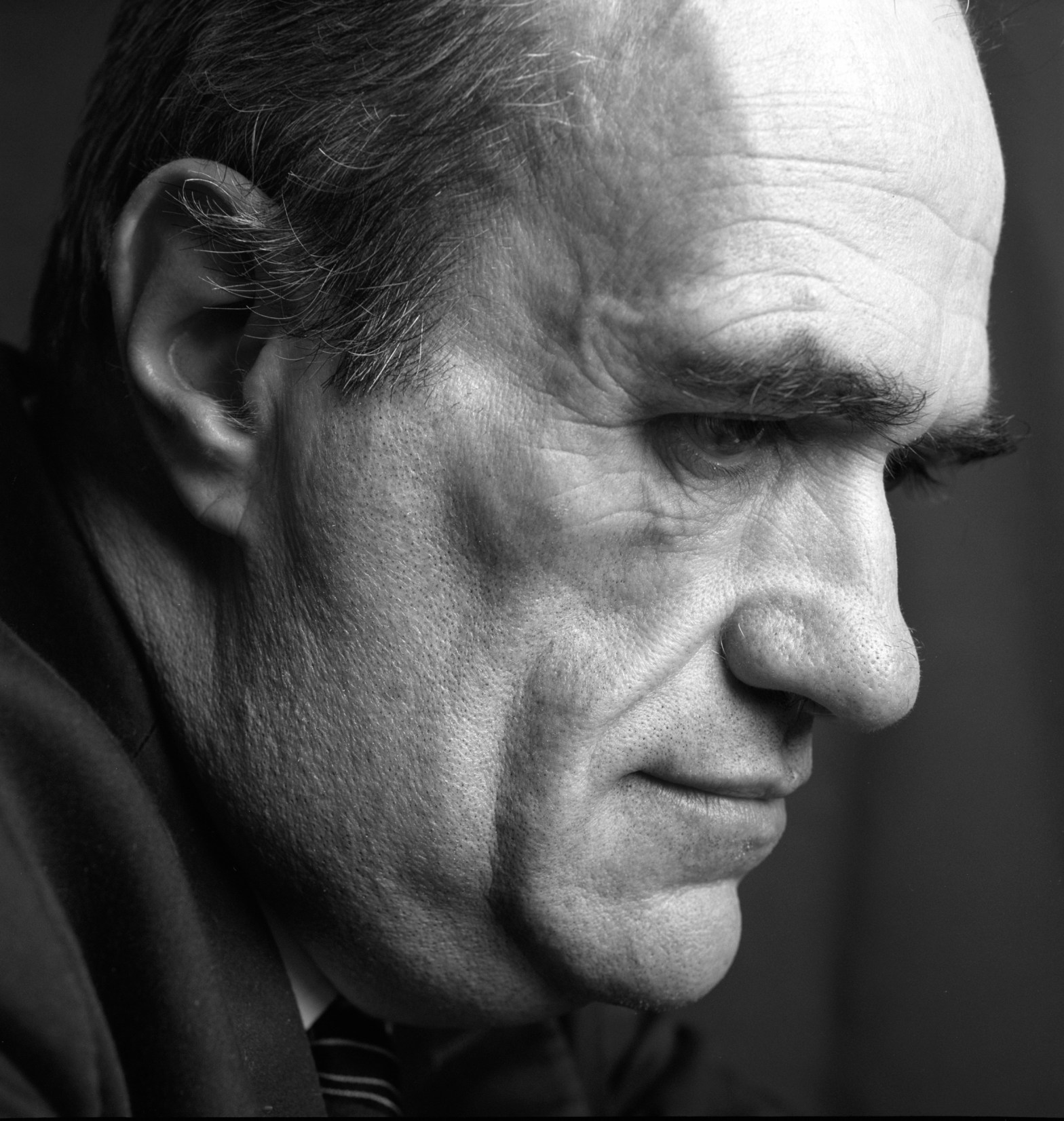

The Irish master discusses the creative impulse, his writing process, and why he finally started writing about queer characters.

It’s almost 5, an April afternoon. I stride into Columbia University’s nearly deserted Philosophy Hall, and climb the stairs, heart thudding from exertion, or nerves, or both. Colm Tóibín is on the sixth floor, waiting for me behind a big desk in his little office. Ahead of my New York visit, a mutual friend put us in touch, and he’s agreed to an interview.

His bibliography bulges with reportage, essays — but it is his fiction that has enthralled me the most. I’ve been a fan for years — ever since I read the Dublin IMPAC Prize-winning The Master about Henry James when I was at school.

Did he always know he was going to be a novelist? I ask.

“No,” he replies, explaining that throughout his teens, he wrote poems. When he moved to Barcelona at the age of 20, this stopped. Not only had the feedback he’d received from readers been less than effusive, the city itself “just didn’t lend itself to anything other than just being out. It was all too exciting.”

He remembers feeling “very clearly that the mechanics of fiction seemed to be so close to the mechanics of journalism — and clunky and not worthy of my attention. In other words, the images were always burdened down by having to connect things and explain things.”

He did attempt a few short stories, however — “which were no good. I couldn’t find a tone for [them]. I was so nervous that I couldn’t get the open, clear rhythm that was like somebody breathing naturally in my opening paragraphs.” He would cram in too much information or insert too startling an image. “It just didn’t work, so I stopped altogether.”

Back in Dublin after three years of teaching English in Spain, he became a journalist, writing for, among others, The Sunday Tribune and In Dublin. He remembers telling friends in 1981 the outline for what would become his first novel, The South. He started working on it tentatively the following year.

Tóibín says many Irish journalists were writing novels, but they were mostly based on their work as journalists. “Mine was the opposite: it wasn’t about that at all. It was about painting, exile, Spain, civil war — it was as far away from what I was doing in the day as possible, really.” He was drawn to that story because of “the poetry”. “Whatever was there first was image-based or language-based rather than about exploring the society or attempting to write a novel that was about the real world. Things came to me as sounds or as as melodies or as images. I couldn’t have gone on writing sentences that were really informative or indicative.”

The South was published in 1990; his second, The Heather Blazing, about an Irish judge, came out two years later. He recalls having dinner with the editor of his first book, who announced to him that she had only just discovered that he was gay, pointing out that homosexuality didn’t feature at all in his novels.

“It just would be unthinkable that you’re going to go on writing novels and this thing that is at the very centre of your being is not going to be explored,” she told him.

Why hadn’t he broached it in his early work, I ask.

“It would’ve been very difficult in Ireland — and indeed in England… the idea of being put into a category and not being able to get out of the category,” he says — especially when he “was interested in history, in many other things”.

“It just would be unthinkable that you’re going to go on writing novels and this thing that is at the very centre of your being is not going to be explored,” she told him.

“But also my own homosexuality was something that I hadn’t come to terms with in many ways. Although I was having probably a whale of a time, I was doing it the way that many gay men did.” He was, he says, “out and in” — out to his close friends, but closeted to the rest of society. “It wasn’t as though there was a huge gay community in Dublin who were all friends of mine and we could all hang out together — it wasn’t like that. So I didn’t have a sense of how I could write about it, what it would look like if I wrote about it.”

“The problem is that once you let the genie out of the bottle, trying to get it back in is hard… so writing [The Master] was one way of navigating that — where I could write about a character whose homosexuality was something hidden and present. And I knew about that, so I could write that book.”

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Before 2004’s The Master — long before it — was the exquisitely erotic The Story of the Night (1996) about a gay man living in 1980s Buenos Aires. Tóibín remembers reading an excerpt at a literary event in London, where the editors and writers present expressed surprise that he was gay. “There was a certain pleasure in that,” he says.

He was reassured by a friend who told him shortly before the book was published: “You cannot be assaulted in this country because of the books you’ve written now and the way in which you’ve presented yourself in this society. You could say anything and it’ll be OK.”

The novel was partly inspired by his time covering the trials of the generals who had ruled over Argentina’s military dictatorship. After a day spent in court, he would drift through the narrow streets of Buenos Aires’ El Microcentro, which was “filled with guys looking at shop windows pretending to be very interested in some suit or other — but actually they were just using the window to see who was stopping and who was coming by. It was the cruisiest place I’ve ever been because there was nowhere else you could go.”

The novel was also, he says, “set in a version of Ireland — in the sense of a society where homosexuality was almost unmentionable”. In 1985 Buenos Aires there were no gay bars; the gay guys he did meet would tell him that no one knew they were gay, that they had a girlfriend they were going to marry.

“I had a pretty good time of it because I was Irish… no one worried about having sex with me since clearly I was going home. I just took full advantage of that situation,” he smiles.

“I can work anywhere,” he says. “I’ll work in a hotel room. Often I’d love to make this room into where I’d live. Put in a top floor with a little ladder and a desk up there and a bed and a little kitchen and a little bathroom and just live here.”

If you think of writing as a form of self expression — a form of pleasure, a form of comfort, a way of comforting yourself, a way of even amusing yourself — I think you’re missing the point.

He sometimes goes to Spain or California (where his boyfriend lives) to write. And then there is Dublin. “I always think someone of my generation, home is where the CDs are,” he grins. “My CDs are in Dublin.”

I can’t resist asking him about the uncomfortable chair he apparently writes at when he’s in Dublin. He groans before I’ve barely phrased the question — it’s come up with painful frequency in interviews over the years.

He explains anyway: “If you think of writing as a form of self expression — a form of pleasure, a form of comfort, a way of comforting yourself, a way of even amusing yourself — I think you’re missing the point. For me, it’s a way of pulling things up and out — guts. Things that have not been spilt before. It depends on memory, on imagination. It depends, for me, on things that are very difficult,” he says. Sitting on “one of those master-of-the-universe swing chairs that are made of some extraordinary fabric that’s soft on the bones — well, I don’t think that would be good for me.”

So, does the chair make him focus? I ask.

“It’s one thing that focuses you. The other thing that focuses you is just not looking up. Just settling down to the fucking thing and doing it.”

If it’s so difficult to do, why does he bother?

“I think that I have some basic urge to communicate levels of feeling — things from the nervous system, and from memory, to other people,” he replies. “It’s a basic urge, it seems to have always been there — that somebody wishes to record or set down feelings or things of what they were like on a given day,” he says. “In the same way as when people went hunting many thousands of years ago, someone stayed behind to paint the hunters on the walls of the cave. It’s a mysterious thing because it really has no material value.”

He says his answer “sounds slightly metaphysical and precious; but there it is, there isn’t any other answer.”

Is there a particular time of day he writes?

No, he answers: “If you have to finish it, finish it. The urge to finish sometimes is a big one, that you’ve really got to try and develop. I can do a lot in a day, but only when I’ve got everything in my head.”

“If you have the character, if you’re me you have everything then because you can work around and you can build up the story. You always will know what they would do, or what they must do in a given situation. Then you can work from that.”

While Brooklyn (2009) developed quickly, his novels typically have a long gestation period — he admits to having four in various stages of development currently. He started working on 2014’s Nora Webster in 2000. It’s closely based on his childhood, on the aftermath of his father’s death. “That was the big one that I couldn’t get an arc for. And also, the material was so personal — giving it up was going to be difficult.” He dreaded “not having that story to tell anymore” — “because once I finished it, I realised I can’t really revisit this material — I have to sort of let it all go”.

The hardest part of the book was a passage where the title character (who was inspired by his mother) sees a vision of her late husband. Tóibín grabs a copy of the book from his bookshelf, and reads it, the words emerging so quietly that my voice recorder barely catches them.

He closes the book. He tells me about how he went alone to Wexford — the setting of the book, where he grew up — specifically to write it. He spent the whole of Saturday at his desk.

“The reward was going to be a big swim. And it started to rain — being Ireland, of course,” he smiles. After writing it, he went swimming anyway. “I stayed in the water for quite some time just thinking, ‘I will never have to do that again; I will never have to do that again.’” Afterwards he packed up the car and drove back to Dublin — he didn’t want to be in the room where he wrote it.

“With that, you can’t do a second draft of it. It’s one of those bits that you write down as though it’s happening in real time to you, now, and you can change words or make little cuts but you can’t rewrite it — you can’t start again; you do it once.” It’s not a vision, he emphasises — “you’re in full control over it. You’re concentrating fiercely; it’s an act of will.”

I ask him if writing something so personal results in catharsis.

“No — you’re manipulating, pulling out and you’re using, you’re not releasing. It’s funny — if anything it hardens it.”

A recent story Tóibín wrote for the New Yorker he based on his experience of hypnosis with one of Ireland’s top psychiatrists. I ask him if therapy has influenced his writing.

“It’s been useful,” he replies. “It gives you a sort of knowledge so you can see things more clearly. So if you’re dramatising things you actually know why you’re dramatising them — or you can see the conflict; you can know why, as you turn a page, you’re suddenly going into this territory — without doing it blindly or foolishly.”

I ask him how time away from Ireland influences writing about his homeland.

“My problem is that I don’t have any real sense of contemporary Ireland. A few times in short stories I can do it, but I don’t have any real sense of the society.” He thinks that’s because “I haven’t had children there and lived in the suburbs and watched them going to school… I’ve been very solitary and I have not had a job [there] for a long time.”

“I think when you get to a certain age it doesn’t really matter where you live. I know people disagree with that — I talked a lot at one point to your compatriot Nadine Gordimer about that. She was very intent, very emphatic about the idea that if you missed the small daily, businesses of a society — not even one that’s changing, but just one that’s there — then you lose a flavour for your book, the things you just won’t know. But in my case, I’m not that interested in societies anyway — as she was,” he says. “The flying in and out has been good,” because returning after time away results in “a sudden re-familiarisation — a smell, the look of something, the sound of someone’s voice, when you’re not used to it”. “If you’re there all the time, you might not feel that as sharply, it wouldn’t seem so stark or oddly interesting.”

“I didn’t plan to start living in America,” he says. “I just got offered jobs and suddenly sort of drifted into it.” He loves “everything about” Columbia. Instead of teaching in the creative writing faculty, he lectures for one semester in the English literature department. Surrounding him are theorists, academics who have written serious critical books. “I’m the writer in the department. I think there was a bit of suspicion to begin with that I wouldn’t know what I was talking about, and that the students wouldn’t be getting value for money,” he says.

On Mondays, he teaches to postgrads a course called Ordeal and self-invention: the heroine from Jane Austen to Edith Wharton; on Tuesdays he gives one on Irish prose to undergrads. Instead of looking at literature through a theoretical prism, “I’m looking at the thing as it’s being made, as though it not been made yet — and looking at what the strategies are to create something.”

Today he explored with his 15 students that sometimes “a novel is a way of rescuing a novel — meaning that half-way through a novel you realise that if I don’t get involved in the rescuing of this book, then I’m going to lose the book. And often it’s because you’ve given characters too much definition, and they’re now only going to live in character for the rest of the book. We talk a lot about not having settled characters”. Henry James realised “he had to soften characters or make characters seem more foolish or give characters moral agency they didn’t have before.”

“You’re talking book all the time,” he says. “It feeds its way back into the books some way or the other. But it also keeps me alive — in the sense that you really fucking worry about these classes before you go into them.”

One of several books Tóibín has edited is the Penguin Book of Irish Fiction (1999). I ask what the common threads tying together the tapestry of Irish literature are.

“We can’t really do domestic bliss, and we can’t end a novel in a wedding,” he says. “There is always a bit of a propensity to break up any peace that’s been had… There’s a problem always with chronology: many novelists feel you cannot handle time directly, that time has to be the first thing you play with — you usurp, you turn around. There’s a lot about death, and dwelling on death and dwelling on solitude and grief.”

“Irish prose fiction tends to be poetic,” he adds. “The sentences are constructed for their sounds, their melody as much as for what they might signify. And so you’re always listening to a rhythm.” This stems from “an aboriginal set of feelings” — “the impulse itself comes from the same impulse as to sing and make music.”

There is something discordant, uneasy about these stories — because “nothing was communal or politically agreed”; “everything was disputed or broken or ready to be burned down — or ready to be erased, including memory.” He can sense the contrast between Irish and English writers “very emphatically” when sharing the same platform. “Their thinking and their speech and everything they’re doing is entirely different.”

“Being in New York is much easier for me than being in London,” he says. In the Big Apple, “nobody has any preconception that if you’re Irish you’re one of two things” — the English either perceive you as “alarming in some odd way, or that you also have a natural talent with words that the entire society has — that words are sort of pouring out of all of you all the time.” The English think “you’re always storytelling and your grandmother must’ve told stories… I hate storytelling,” he says, defining the form as “arising from an oral tradition which is unmediated by a literary tradition and which makes its way unstructured onto the page as though it’s a sort of form of flowing water”.

“You’re constantly trying to get them to stop fucking making a cliché out of you.”

Nora Webster was published by Penguin in the UK, and Scribner in the US. An edited version of an article which was originally published at AERODROME on August 31, 2016.

An edited version of this Q&A appeared in the July/August 2019

An edited version of this Q&A appeared in the July/August 2019