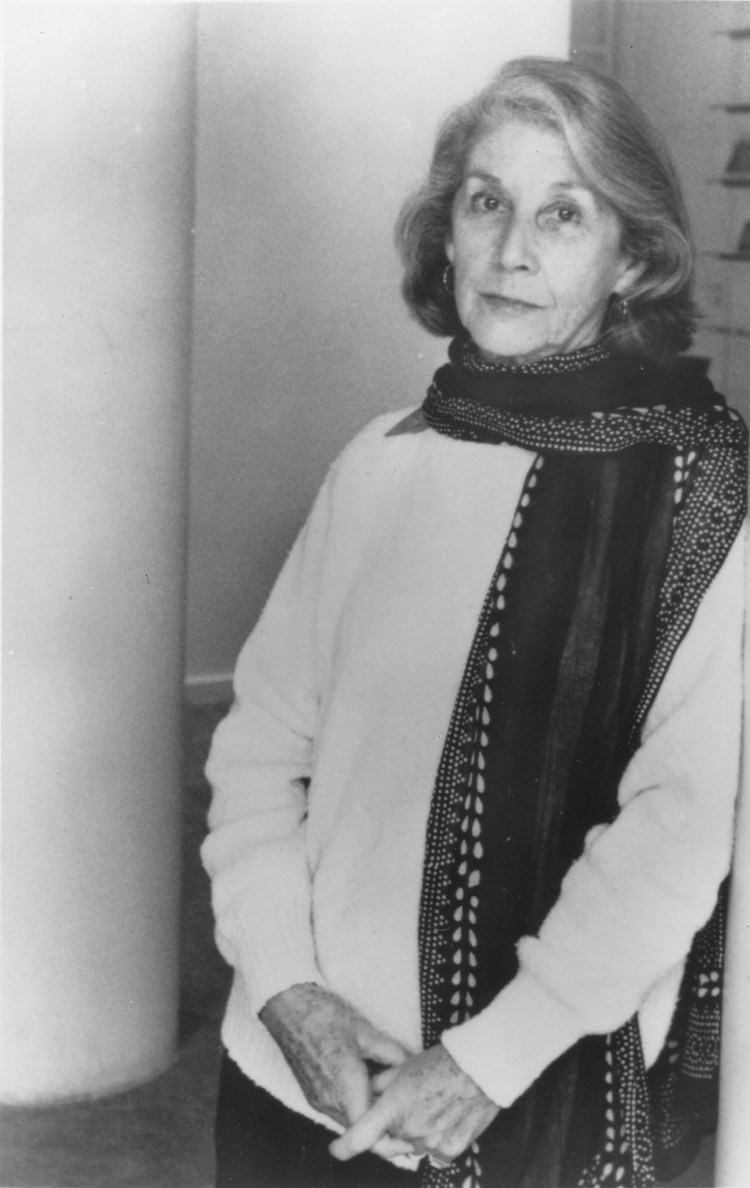

From the archives: a chat with the late Nadine Gordimer in which the Nobel Laureate discussed her final novel, banned books and her life’s big regret.

I am standing in a quiet street in Johannesburg’s Parktown, outside high white walls, topped by mean black electric wiring. There is no doorbell; just two gates. Fortunately, there is the sound of unlocking; one starts whirring open.

Nadine Gordimer comes out into the driveway of the home she’s lived in since 1958. She is tiny, a little wizened, but still beautiful, elegant. Her Weimaraner, Bodo (“a German name for a German dog”), struts around her feet, silvery and sleek. I confess I own one too, and she’s relieved to hear the puppy is female – the bitches make better guard dogs, she says.

Gordimer leads me gracefully onto the gleam of the hallway wooden floor, to the sitting room. Lush garden brushes against the windows, light falling on the book-lined shelves, the white walls. A gentleman wearing a khaki uniform and blood red sneakers brings in tea and ginger biscuits.

“No we don’t want you because you’ll be begging for biscuits,” she tells Bodo as he slinks towards us. I fare rather better: she insists I take several.

“I’m in real trouble now,” she says crisply. “I love my two old Olivettis [but] they don’t make the ribbon for them anymore. So now I have bought a computer. It’s standing there looking at me – I’ve had it about a month; I haven’t learnt to use it yet. Maybe I’m too old to learn; I don’t know. But a friend of mine who is a journalist – she just says this is nonsense and she’s going to teach me.”

It’s ironic that Gordimer’s latest novel, No Time Like the Present, has been tapped out on a technological anachronism. Ironic because this vast, sprawling work is perhaps the most powerfully canny exploration of modern South Africa yet, tracking the trials and tribulations of the beloved country since 1994 through the eyes of Steve and Jabu, a married couple, and their friends and fellow comrades who fought with them against apartheid in the ANC’s armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe.

It is all there: the tendrils of corruption steadily unfurling through our public institutions in the Arms Deal and other scandals, the madness of Mbeki’s Aids denialism, the strikes, the “housing whose brand-new walls crack like an old face”, the persecution of refugees by an increasingly discontented population.

“One can be – and I am – very concerned for the future of the country but I think this is based on a curious fact for all of us, those of us who were involved in the struggle, every consciousness that one had was directed to get rid of apartheid,” Gordimer says. “Unfortunately we were too preoccupied; we didn’t think of the likelihood of the problems afterwards. We found that freedom is not automatically ‘a better life for all’ – that famous phrase that we have.”

“In the last two years, I think, there has been an acceleration of extremely worrying things. I mean the rise of unemployment. Another thing I think terribly worrying is the standard of education. Every day there’s something else that is very worrying. The news that comes today: they haven’t got any drugs in several hospitals. We didn’t, of course, think that there would be corruption the way there is. We have to accept what it is now and do whatever we can about it. Of course, I am particularly concerned, in addition to these other things, by the two bills – by the media tribunal and the secrecy bill. We’ve got to fight that in every possible way.”

Having had three books banned by the apartheid regime, and felt the pain of being denied “having a conversation with your own people”, it’s no wonder that Gordimer feels strongly about the ANC’s intensifying assault on the freedom of speech.

“We must be free to criticise. In the Constitution there are provisions that indeed protect us from, for instance, revealing military secrets. These I think for me are the only defendable ones – that has to do with our security. Bearing in mind, who is going to invade, my dear? We still have the strongest army in the continent, the greatest resources of defence, so are the Chinese going to come here?” she laughs. “So the idea we’re under threat is a false one and it mustn’t be used to frighten people into accepting this bill. The real purpose of this bill – it sounds simplistic to say it – it is to protect corruption which is rife from the very top, right through our government and through our commercial institutions.”

Gordimer believes the personal and political are inextricably linked, a philosophy that has dominated her oeuvre and something she continues to grapple with in her newest book. “What is a political writer – someone who writes political analysis? If you’re born into a situation of conflict, you are automatically one,” she says. “On the personal character level, it may seem such a political kind of cliché to have a black and white – a mixed – couple. But what I think I have done in that book is at the personal level even in a strong love relationship there are certain differences, they come even from being born into a different language, that you have to deal with. It’s another coming together; it’s not a political one, but it’s imposed by the politics.”

Unlike Steve, a university academic who endeavours to learn his lawyer wife’s mother tongue, isiZulu, Gordimer says, “The big regret in my personal life is that I didn’t learn – and I have not learnt – an African language. And still, in this very room when my black comrades were here and I go out to make tea or to bring a drink or something, I come back and they’re talking away to each other and I am in a foreign country.”

Despite the sacrifices made in their fight for freedom – and the bonds linking them to the liberation movement and its members – the couple at the heart of the novel plan a move to Australia. For them, the Rainbow Nation had been robbed of its promise by the greed of their erstwhile comrades, who now form part of a powerful elite. Gordimer shares her characters’ intimate dismay at the way graft has become entrenched in South African public life.

“I have a very personal view of corruption because some of these people have been intimate, close friends of mine and some of them indeed I have been connected with and did my small share of protecting or defending – I defended in the Delmas trial and so on. I couldn’t believe – I’m making myself believe – because I’ve been thinking and thinking about it, how could they become like this. It’s a tremendous disillusion.”

She speculates that rampant malfeasance is a backlash to the centuries of systematic oppression that resulted in “people who had everything taken away from them, whose whole personality was cemented over”, their economic rights denied. “It doesn’t say one approves of it,” she points out carefully. “It’s just a reason and it isn’t excusing it.”

I ask what gives her this sensitivity, a determination to see the shades of grey instead of stark black and white. “I never think about that – that’s for critics to think about, not me,” she answers. “I just write what I have to write. Because to me, my writing and anybody else’s that has any meaning for me, it’s a search for the meaning of being human in whatever circumstances have come along. The meaning of it is the discovery of life as a human.”

“I can only think that those of us who write trying to discover what beliefs we believe are the truth about ourselves and everybody else and our reactions – that reading about this makes you think. My own development as a writer has become through reading and being woken up to think by novelists, poets, short story writers. If you read in translation, when you were 17 or 18 years old, Dostoevsky, you begin to understand that there is such a thing as evil, it’s not just a biblical thing; it’s in us,” she says.

“I’m a passionate reader and have been since I was six years old. My mother read to us – to my sister and me – when we were little.”

Her mother made friends with the librarian at her local library, and the young Gordimer was able to wander around, reading whatever took her fancy. At a family friend’s house, she discovered a copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H. Laurence (then still banned), which she devoured, chapter-by-chapter, each Saturday night.

It is perhaps this curiosity, this thirst for words, that made her begin writing at the age of nine. But she refuses to diagnose what urge led her to first put pen to paper, saying, “If you’re going to be an opera singer, you’re going to be born with certain vocal cords. I’m sure you haven’t got them and I haven’t so we’re never going to be at La Scala even if you can sing a little and you go to have your voice trained for years, you just haven’t got that. Now, I don’t know what we fiction writers and poets have, but there must be something – I suppose it’s in the brain. That’s the only explanation I can give.”

Her political awakening coincided with her growth as a writer. “I was 11 years old when I first discovered that there was something very strange about the attitudes of my family, myself, my convent where I went to school. I then became aware and began to have connections across the colour bar and they came about, oddly enough, very often through my learning to be a writer. So that I met, for instance, the great Es’kia Mphahlele. He and I were both teaching ourselves to write at the same time. So I had a bond with him; I could talk to him in a way that I couldn’t talk to the young whites with whom I went dancing or jolling around. It answered some need in me.”

I ask her if writing ever gets any easier. “No, of course not,” she says firmly. “It changes in reaction to what’s happening to you in your personal relationships, to you in your relationship with the world.” And is she already working on another book? “Well, I’ve just finished one,” she says a little indignantly. “I’m very old now.” She says her novels normally take her two to three years to complete. “I will stop writing when I know that it’s not what I would think any good.”

It could be the benefit of age and the accumulation of wisdom, but notwithstanding her deft unpicking of this country’s woes, her view of SA’s future is edged with optimism. “I am not a prophet. I can only set my mind to one fact – if we managed to defeat apartheid – and apartheid was only a culmination of racism that came with the precursors of colonialism in 1652 – surely we mustn’t fall easily into despair.”

This sentiment is echoed in the closing pages of the novel:

Brought down the crowned centuries of colonialism, smashed apartheid. If our people could do that? Isn’t it possible, real, that the same will must be found, is here—somewhere—to take up and get on with the job, freedom. Some must have the—crazy—faith to Struggle on.

At the end of the interview, we tour some of her bookshelves. She tells me to read Marcel Proust; she taught herself French so she could read his original work. And there are others I’m instructed to try: William Plomer, Graham Greene. She feels she’s outgrown Virginia Woolf; however, she wants to re-read Ulysses by that other modernist, James Joyce.

At 88, she’s still a sponge: absorbing, absorbing. She enjoys Wasafiri literary magazine; reads three papers at the weekend, the New York Review of Books and other publications sent to her.

She sees me out. We’ve run over time, and her retired domestic worker is waiting in the spotless kitchen, having journeyed from the North West province to see her. The gate opens; my driver is waiting. She gently waves goodbye.

This interview was first published in Wanted magazine’s April 2012 edition. Gordimer passed away in 2014.

The first few days were the hardest. My body was still slowly acclimatising to carrying the weight of my backpack and to walking long distances. Towards the end of the second day I felt particularly tired and uncomfortable – or so I thought. When I stopped thinking about what I was feeling and simply started feeling – honing in to observe, minutely, the sensations in my buttocks, my thighs, the discomfort seemed to melt away. A slight heaviness remained, but it felt as if I could carry on for miles. As my Camino progressed, I would return to this, letting go of words, stories, ideas – and just feeling, just walking, just being.

The first few days were the hardest. My body was still slowly acclimatising to carrying the weight of my backpack and to walking long distances. Towards the end of the second day I felt particularly tired and uncomfortable – or so I thought. When I stopped thinking about what I was feeling and simply started feeling – honing in to observe, minutely, the sensations in my buttocks, my thighs, the discomfort seemed to melt away. A slight heaviness remained, but it felt as if I could carry on for miles. As my Camino progressed, I would return to this, letting go of words, stories, ideas – and just feeling, just walking, just being.