Sultry dusk descends over the Art Deco change rooms at the Clube dos Empresarios – the businessmen’s club – as the courtyard lights shimmer on the pool. I’m sitting with a 2M beer, and the fabled Petula Clark is exhorting me from hidden speakers not to sleep in the subway. Shirley Bassey soon follows with luscious Goldfinger. Can you blame me for feeling like Sean Connery – or at the very least one of Graham Greene’s seedy spies?

Nostalgic and unashamedly sentimental, this is the sound of LM Radio. Every day, it ripples across Maputo – in taxis, cafes and government offices, even. In a nod to the golden oldies that form the bulk of its playlist, the “LM” today stands for “Lifetime Memories”. 50 years ago it stood for something else: Maputo’s former name, Lourenço Marques.

The man responsible for relaunching LM Radio, which was shut down upon Mozambique’s independence in 1975, is Chris Turner. “Radio has been my love since a very young age,” he says when we meet at the station’s studio in the Marés shopping centre. He remembers his dad, a radio enthusiast, tuning into the likes of the BBC World Service and Voice of America. “I was fascinated by listening to all these stations from faraway.”

By the time he was eight, he was building his own radios. He quickly became a fan of the original LM Radio – which he would re-broadcast from a homemade transmitter on medium wave to the rest of Fish Hoek, where he lived.

Enthralled by pictures of the palms and beaches, “I used to imagine LM as a sort of island paradise,” he says. “It captured the imagination.” He loved the Sixties pop and rock it played – including the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Beach Boys and Manfred Mann.

The music was completely different the SABC’s “very sanitised” fare: “anything that had any sort of sexual or revolutionary innuendo was completely banned” by the state broadcaster. Across the border – and beyond South Africa’s censorious jurisdiction – LM Radio was able to play banned music – including songs by black South African and African American artists, as well as those who publicly opposed apartheid.

Established in 1935, LM Radio was Africa’s first commercial radio station – a collaboration between a group of amateur radio enthusiasts, Radio Clube de Mozambique, and the entrepreneurial South African GJ McHarry – who had been inspired by the success of independent Europe-based stations. In the 1930s, these were being beamed across to the UK where the BBC had a monopoly over the airwaves – rather like the SABC did in South Africa at the time.

The station was a huge hit, its profits going towards the building of a Radio Palace – featuring some of the most advanced broadcasting kit in the world – in central Lourenço Marques.

“The hit parade as we know it was actually invented at LM Radio,” Turner says. Previously, chart toppers were played by a radio’s orchestra. Station manager David Davies (who had been at Radio Normandy before World War 2) decided the original tracks should be played instead. It was the first station in the world to do this.

“In 1969, market research in South Africa said there were 2.4 million white South Africans listening to LM Radio. That was bigger than the listenership of the SABC. That’s bigger than any South African radio station today in terms of listenership,” Turner says.

In 1973, the SABC bought the station, concerned that the fierce war of independence being waged by Frelimo against Mozambique’s Portuguese rulers would ultimately lead to the station falling into unfriendly hands. After independence, the station was then shut down.

For Turner, reviving the station 50 years later has been about serving a baby boomer listenership that has long been ignored by youth-obsessed South African stations. In recent years, music from the 1960s and 70s has scarcely featured on our airwaves – and he was determined to change that.

In 2010, after five years of painstaking preparation, the new LM Radio got its permanent Mozambican FM frequency, 87.8, broadcasting across an 80km radius from Maputo (including across the border in Komatipoort). A Maseru transmitter means it can also be heard on 104FM in the eastern Free State. It can be streamed online or on its smartphone app and is available on satellite from both DStv and Open View. Gauteng listeners will soon be able to listen to it on 702AM, when its Welgedacht transmitter gets switched on later this year.

“The listeners that we have in South Africa like the nostalgia aspect of it” and tend to be above 45, “whereas here in Maputo, nearly half our listeners are under the age of 25,” he says. “It’s because we’re different. Nobody else plays the music that we play – they all play this head-banging doef-doef.” It’s perhaps not surprising, then, that the station was voted best radio station in Mozambique for three years consecutively.

“We’ve stayed true to the original model, which is an intimate presentation style. We have one presenter in the studio, except for our Saturday morning programme where we interact with people in the shopping mall so we have two… We talk to you… We don’t encourage voyeurism – in other words we don’t have two people sitting in the studio talking about their lives and what they do – it’s about the listener. It’s more music, less talk.” There are 12 or 13 tracks an hour – whereas other SA radio stations typically play only seven or eight.

“Mozambique has been very good to us. Initially we were told by all sorts of people we’d have trouble licencing an English language radio station, and we’d have trouble with the name ‘LM Radio’. We did have some opposition, but at the end of the day the opposition was nowhere near as bad as people” said it would be, he says. “I’m not the sort of person that gives up” he laughs.

How to get those golden grooves:

Maputo, Ressano Garcia, Ponta do Ouro: 87.8 FM

Maseru: 104 FM

Open View HD (OVHD): Audio channel 602

DSTV: audio channel 821

Planned launch in Gauteng April 2017: 702kHz AM

Online: lmradio.net

40 years later, he’s back on air

For Nick Megens, hosting LM Radio’s breakfast show is “totally full circle” – because it’s what he was doing more than 40 years ago on the original station. The Dutch son of an itinerant WHO official, he got a DJing gig in his early twenties after a chance encounter with two LM Radio presenters at Lourenco Marques’s English Club.

In 1973, after three months of training, he was given “the graveyard shift” – playing tunes in the early hours of the morning, which he loved. “It’s amazing how many people listen at night” he says – such as nurses and firemen. He was then promoted to the breakfast show.

“Living in Mozambique was paradise,” he says. “The way of life was simple.” After finishing each day, he would head to the beach, have lunch, then nap until 9pm. “Everything was cheap. Even on our small salaries that we got, we could afford to go out every day.” Back then a dozen prawns back then cost about R2. He would dine at Peri Peri (which still serves up its legendary chicken today) or drink at hotel bars. Sometimes visitors to the city would pop into the studio, and take the presenters out for dinner; afterwards they would head to the city’s strip clubs (then banned in South Africa) that featured exotic dancers from all over the world.

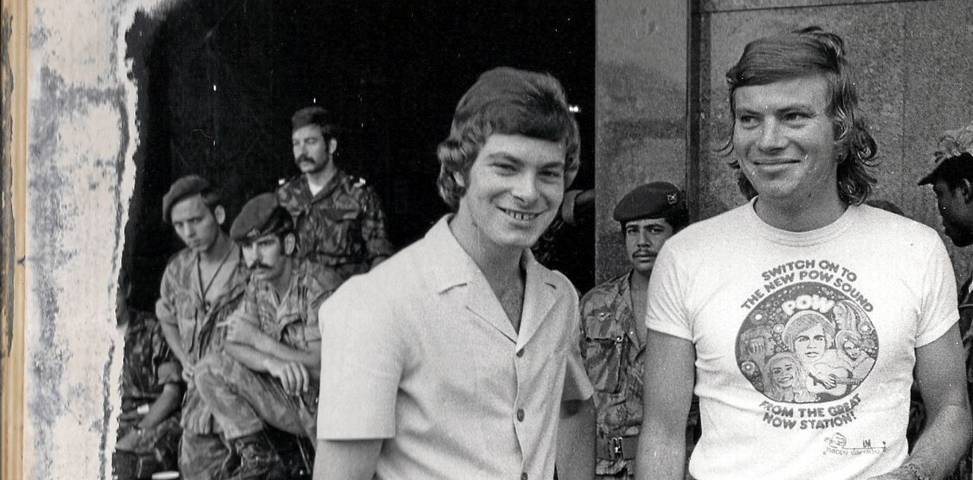

In 1974, disgruntled Portuguese settlers staged a coup against their own government in protest at its decision to hand power over to FRELIMO without elections. They took over strategic points such as the airport and the radio palace. Along with station manager Gerry Wilmot and the newbie presenter John Novik, Megens took turns – three hours on, three hours off – to keep LM Radio on air. “We hardly got any sleep and, of course, you had to wash in a hand basin, you didn’t have any clean clothes. It was crap.”

The rebels gave them bags of oranges and occasionally a loaf of bread – as well as piles and piles of cigarettes. “They thought probably we’d smoke ourselves to death,” he says. You were allowed to leave, but “if you left, you weren’t allowed back in,” and so they kept at their posts. The Portuguese army successfully took control of the building 10 days later. “There was a lot of fighting going on with guns being fired, and then there were a couple of grenades lobbed into the building. I’m no hero – when you hear a grenade go off, you actually crap your pants.”

A year later, the four-month old FRELIMO government nationalised LM Radio’s facilities and shut the station. The SABC’s replacement was Radio 5 – today known as 5fm. Megens, as breakfast show host, was the first presenter on air. The studio (at the SABC’s then headquarters in Commissioner Street, Johannesburg) was swarming with journalists; the champagne was flowing. Megens recalls the SABC chairman standing behind him, giving him a shoulder rub, telling him, “‘Jy doen goed seun, jy doen goed.’ [You’re doing well, son.]”

“Of course I go and bloops it all up by saying ‘Dis nou sesuur en jy luister na LM Radio… ek bedoel Radio Vyf! [It’s now six ‘o clock and you’re listening to LM Radio… I mean Radio Five!]’,” he recalls. Luckily “everybody was laughing”.

An edited version of this feature appeared in the 5 February 2017 edition of the Sunday Times.

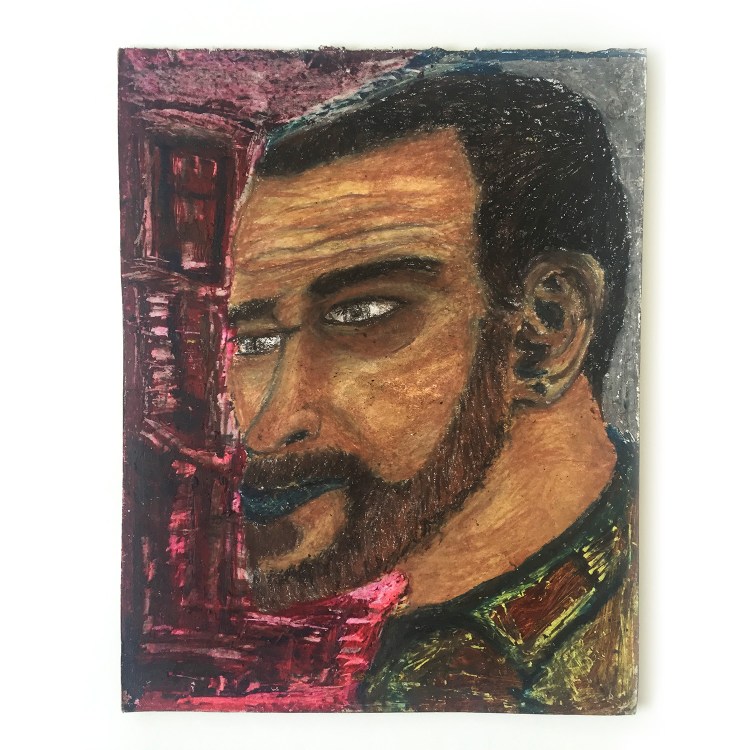

This is a city resident who often walks through Government Avenue. I was inspired to sketch him because of the expressions on his face while he listens to music. The expression on his face is determined by the asymmetrical design of his eyes and his narrow mouth. The well-lit face is framed by badly behaved hair, accentuated with restless brush-strokes and scratches. I drew this portrait with mixed media – wax, paint, charcoal and pastels.

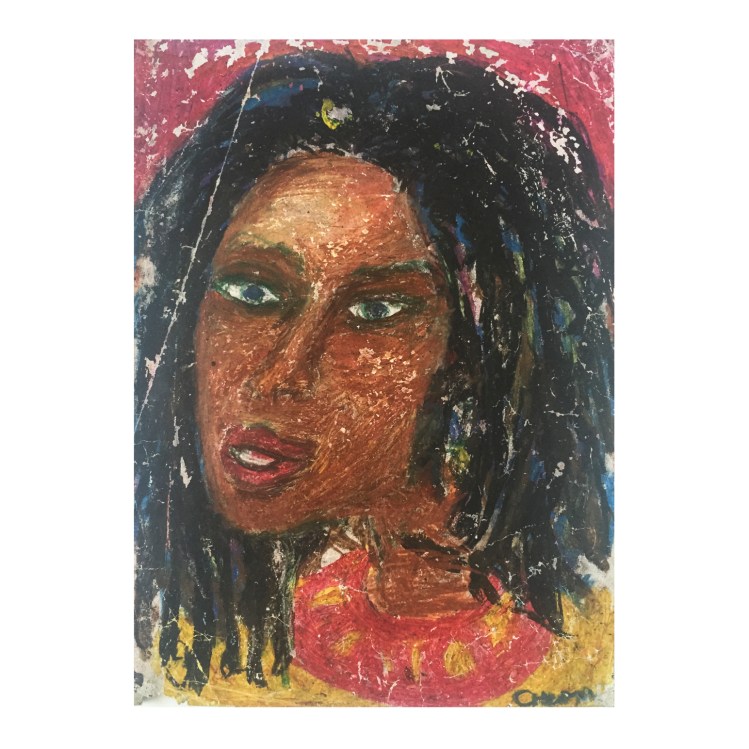

This is a city resident who often walks through Government Avenue. I was inspired to sketch him because of the expressions on his face while he listens to music. The expression on his face is determined by the asymmetrical design of his eyes and his narrow mouth. The well-lit face is framed by badly behaved hair, accentuated with restless brush-strokes and scratches. I drew this portrait with mixed media – wax, paint, charcoal and pastels. I met Tumi a year ago and we became close friends. She often lives here with me on the street. She sometimes goes home and stays for few days but is always back. She shoplifts to support her heroin habit. She has been on it for almost 10 years and has been arrested three times since we became friends.

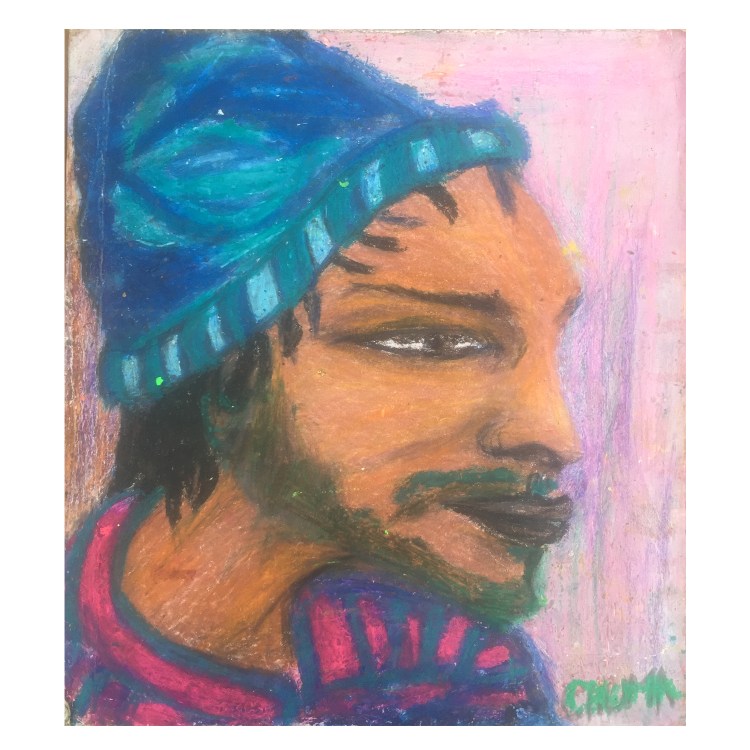

I met Tumi a year ago and we became close friends. She often lives here with me on the street. She sometimes goes home and stays for few days but is always back. She shoplifts to support her heroin habit. She has been on it for almost 10 years and has been arrested three times since we became friends. Rasta is in his late twenties. He has a girlfriend who is HIV positive. She doesn’t take her meds and they are both tik addicts.

Rasta is in his late twenties. He has a girlfriend who is HIV positive. She doesn’t take her meds and they are both tik addicts. Dikie is a homeless man who’s been living on the streets of Cape Town for 40 years. I’ve grown fond of him. He makes a living by resourcefully collecting cardboard boxes where he can, then exchanging them for cash at the Service Dining Room. He has lost two sons to TB. He is very shy, and as I know him, he usually just quietly greets you, but is mostly on his own.

Dikie is a homeless man who’s been living on the streets of Cape Town for 40 years. I’ve grown fond of him. He makes a living by resourcefully collecting cardboard boxes where he can, then exchanging them for cash at the Service Dining Room. He has lost two sons to TB. He is very shy, and as I know him, he usually just quietly greets you, but is mostly on his own.

At the end of July last year, I moved out of the flat I was sharing in Cape Town and became a nomad. Since then, I’ve visited Lesotho, Malawi and Zimbabwe once, Mozambique six times, and Swaziland five. In South Africa, the past year has seen three Kruger trips, a traversing of the Waterberg biosphere reserve, a few Cape Town visits, and too many times in Joburg to count. But the very first stop, marking the beginning of nomadic life, was a night spent at

At the end of July last year, I moved out of the flat I was sharing in Cape Town and became a nomad. Since then, I’ve visited Lesotho, Malawi and Zimbabwe once, Mozambique six times, and Swaziland five. In South Africa, the past year has seen three Kruger trips, a traversing of the Waterberg biosphere reserve, a few Cape Town visits, and too many times in Joburg to count. But the very first stop, marking the beginning of nomadic life, was a night spent at